The phrase "financial inclusion" has been used quite liberally over the past several years. Especially when you read about digital platforms, services, or apps that claim to offer low-income earners across Afrika financial services that were previously inaccessible for them.

However, when financial inclusion is mentioned, when you look at what is being offered, it is either some flavor of mobile money, mobile payments, or mobile banking service whose per-transaction fees are still quite high (compared to just using cash). Alternatively, what is being offered are microloans with administration fees, interest rates, and personal data privacy terms that make the Sicilian Mafia’s terms look charitable.

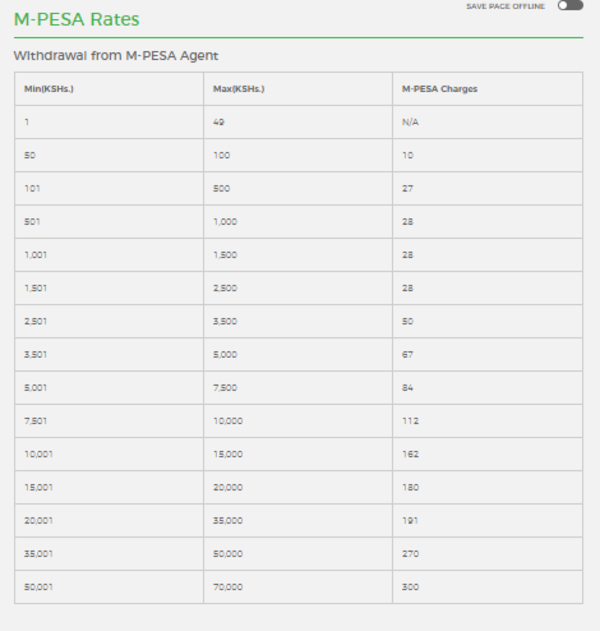

Predatory transaction fees

One example of well an intentioned financial inclusion digital system whose fees are not really predatory but had me raising questions about who the target market is is M-PESA in Kenya. If you look at the M-PESA transaction fees as supplied by Safaricom, you realize that, as a percentage of the amount being sent or received, smaller amounts (e.g. KSh 1,000) attract a higher percentage transaction fee compared to sending or receiving KSh 70,000. In this specific example, sending KSh 1,000 costs 2.8% of the amount being sent in transaction fees compared to 0.004% when sending KSh 70,000.

Why do I mention this?

Because oft times, if not all the time, when digital financial inclusion is mentioned, it is mentioned as benefiting poorer people. In this example, it is poorer people send and receive lots of smaller amounts every day compared to relatively larger amounts such as KSh 70,000.

However, M-PESA and other mobile money services are nowhere near the worst examples of the ugly side of financial inclusion.

Digital microlending apps

The worst culprits are the new digital micro lending apps that have taken Kenya and parts of the continent by storm. If you do the mathematics quickly, you’ll realize some of these loan sharks which constantly market themselves as financial inclusion champions, sometimes come at a cost of 100% when annualized.

With such fees and interests rates, given that they are often given out for a maximum period of 60 days, they quickly get customers into a cycle of debt slavery as immediately after they pay back the principal and interest, they are running low on cash flow and immediately request a new loan from their digital lender. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out where such a cycle leads to.

The predatory practice is nothing new. I’ve seen this in South Africa before the National Credit Act (NCA) became law where micro-lenders, especially the short term loans (max. 3 months repayments) would pad upon the administration fees side (which in many cases would be more than the interest to be paid back) while keeping the interest rates within reason. Since the introduction of the NCA in South Africa, such practices have been kept at a minimum as the act prescribes the amounts that lenders can charge.

Although I often hesitate towards suggesting government regulation of any industry, perhaps it is time Kenya considered similar regulation.

— By Tefo Mohapi