In 2013, the government of Kenya promised to issue laptops to all pupils joining primary school. This was made as an election campaign pledge, and it was one of the most expensive political promises ever made. It would involve issuing laptops to every new batch of pupils joining class one every year.

The aim of the project was to promote digital literacy and prepare young learners to thrive in an ICT-based economy.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the government started following through with the promise. However, it was no longer laptops, but tablets. The reality had slowly sunk in that there was no way the government could issue delicate laptops to grade one kid, preferring to use tablets that were specially designed for the kids.

Six years after the project was announced and three years after implementation, the project was silently retired. In fact, there was no official announcement about the same. Only the sharp-eyed budget analysts discovered that the government had allocated zero shillings for the project, signaling its end.

What went wrong?

Many things went wrong with the project, because as we will see, technology for the sake of technology is not a good idea, and digital inclusion cannot be attained while ignoring other basic needs.

Most politically motivated promises are done without regard to many basic principles of public policy formulation.

This project was bound to fail for the following reasons:

- It would be extremely costly to run the project. This was actually going to cost more than all the other costs associated with free primary education currently offered by the government.

- The lack of skilled personnel to run the program was a major hindrance. Most of the teachers were not very computer literate, and a one-week training by the government would not make them experts when the children they were supposed to teach could easily outdo them in using smartphones and tablets. The content was also not ready and it delayed the launch for quite a long time

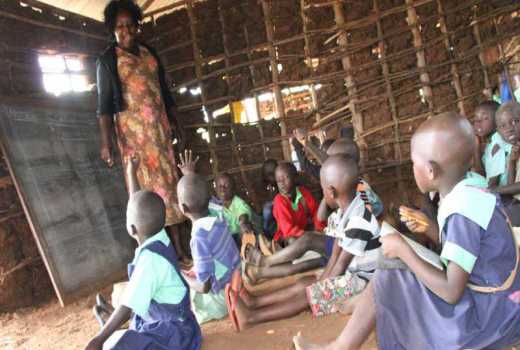

- The priorities were wrong from the beginning. Schools lack teachers, classrooms, connection to the grid, and in some places, there are no schools! It is also common for children to drop out of school due to a lack of books or even food.

- Lack of requisite infrastructure. Only 10% of schools were connected to the grid, while 50% were far away from the national grid. Schools also lacked the facilities to safely store the devices, considering the many cases of school break-ins where books were being stolen.

- Lack of support mechanism when technology failed. This left both teachers and learners stranded, and often having to wait for a long to receive technical support.

What could have been done differently?

The goal of the project was to impart digital skills to students. It was, by all indications, a noble plan. However, as it stands, there could have been a better approach to the same.

One way would be to build computer labs in all high schools in Kenya. This approach would work better since the students already have literacy and numeracy skills. As some people had also suggested, the labs could also be used as community centers to provide the same skills to people in the neighboring communities during holidays or in the evening. The cost would be affordable.

While the government tried to make the most of the project by having the tablets locally assembled, there was little transfer of skills involved. A conversation with one of the people involved revealed that all the parts of the devices, including the plastic covers, were imported, and their only duty was to plug in parts together.

The project failed.

— By Jacob Mugendi