Stephen Donald Birch, a real estate developer, was among the first handful of people to ever be charged for spreading fake news (misinformation/disinformation) under South Africa's amended regulations of Disaster Management Act which was aimed at helping the country contain the spread of COVID-19. In a video he distributed on social media in 2020, Stephen claims that the COVID-19 test kits that South Africa was about to use for mass screening and testing were contaminated.

He further advised people to refuse to be tested. Stephen was arrested and later released with a warning for his spreading of disinformation and misrepresenting the South African government’s efforts regarding COVID-19.

Believing and even producing fake news (to learn the difference between misinformation and disinformation, listen to this discussion with Dr. Vukosi Marivate who is a Data Scientist) doesn’t seem to discriminate on whether one is wealthy or poor, educated or not, or even access to the Internet (i.e. the vast amount of information that you can use to fact-check).

It seems that it is all about narratives, and very little about facts.

Why narratives trump facts

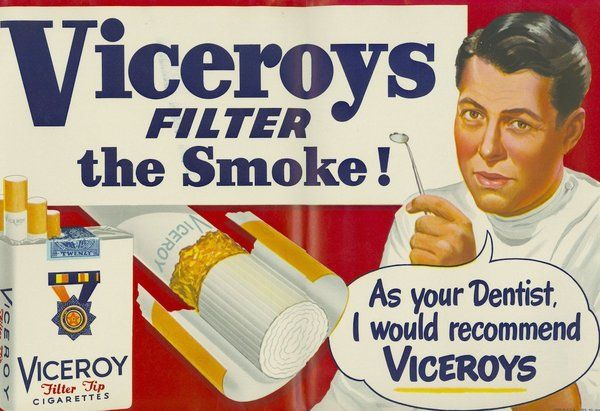

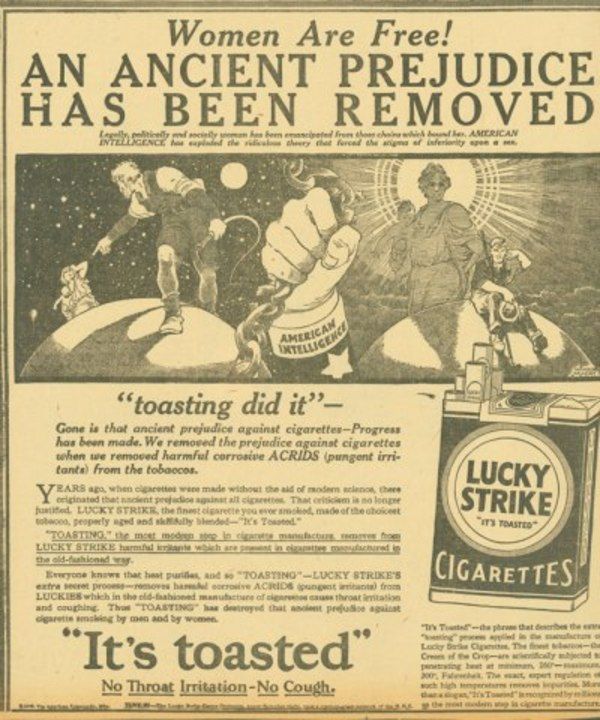

As someone who studies narratives and tries to deconstruct what makes narratives trump facts, over the years I have been studying the works of Dr. Ajit Maan and Dr. Howard Gambrill Clark (to name a few), I have come to realize that several ingredients make narratives, even the most false and outrageous ones that can easily be proved to be fake with just a simple Google Search, to be believable and go viral.

The first and arguably most important ingredient is that it must be a story, as opposed to presenting facts and data. The more emotions in the story, even better. It seems we somehow, by default, we as humans connect better with stories than we do with data.

Secondly, a narrative (even fake ones) appears to persuade more easily if we already hold a certain bias for the story being told, therefore, it merely confirms our bias - what we already, at some level, factual or not, held as true. Lastly, if somehow the person trying to peddle a fake news narrative manages to make you see yourself as part of the story, even better, you are even more likely to believe what they say.

Narrative warfare

This is by no means an exhaustive list of what makes fake news narratives so believable. However, I hope it gives you an idea of how to evaluate any new narrative you come across to ensure that you are not being hoodwinked.

Now, imagine adding the speed and scale of social media to a fake news narrative, now you understand how easy it is for such narratives to find their target audience that in turn will help them spread further.

You now understand, I hope, why some people can be fooled by different narratives including the one that says that 5G is responsible for spreading COVID-19.

— By Tefo Mohapi