By Tefo Mohapi

South African authorities have admitted to conducting mass surveillance on all communications. This was revealed in the former State Security Agency Director General Arthur Fraser's affidavit and other documents filed in 2017 during a court case relating to amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism - a South African non-profit investigative journalism organisation.

What is even more eyebrow raising is that the mass surveillance is said to have dated back as far as 2008 as was revealed during the Matthews Commission ministerial enquiry.

In the affidavit, South Africa's State Security Agency stated that "the Signal Intelligence collection process is informed by the National Intelligence Priorities, which include imminent and anticipated threats. It also covers information about organised crime and terrorist related activities. Bulk [surveillance] also deals with areas like food security, water security and illicit financial flows.”

What has also been revealed, as Privacy International reports, the South African government conducted the "bulk interception of Internet traffic by tapping undersea fibre optic cables." Given that there are several such cables on South African shores, it is not yet clear is such mass surveillance was limited to some of the undersea fibre cables or the State Security Agency actually tapped Internet traffic on all of them.

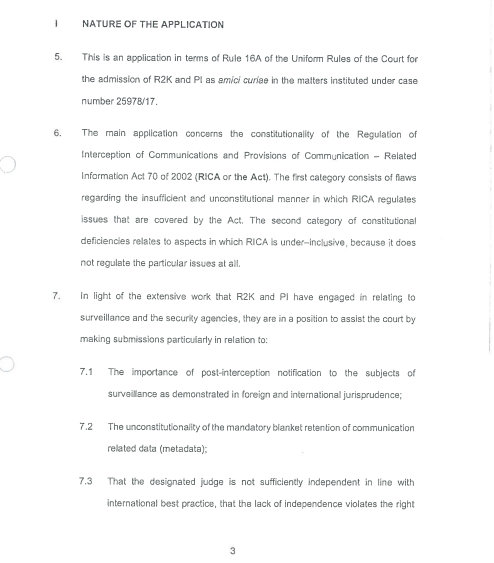

Automated information collection

More worrying is that, despite SSA saying the automated information collection was directed at foreign communications that are a threat to the state security of the country, even they admit that it is impossible, without human intervention, to determine whether any communication passing through undersea fibre cables is of foreign origin or not.

This in turn means that the SSA has been collecting information and communications of South Africans without the necessary permissions. Such mass surveillance is probably unconstitutional and illegal.

Also worrying is that the SSA has said that such surveillance and data collection is "common practice" globally.

Some time during 2017, amaBhungane initiated legal proceedings after they became aware that the SSA and those related to it had been recording their editor, Sam Sole’s phone communications for a period of at least six months in 2008 during South Africa's ‘Spy Tapes’ era. This then led to further widespread revelations about widespread and indiscriminate surveillance by the SSA.

More details on South Africa's mass surveillance

Reading some of the court documents related to the State Security Agency and the case brought against it by South Africa's amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism, you will come across the name Murray Hunter. Hunter at the time when these court cases were taking place, was working for a Right2Know, a South African civil rights organisation that, together with Privacy International, intervened on the case against the State Security Agency as friends of the court.

I decided to quiz Hunter so he can shed more details on this mass surveillance, what it possibly involved and it means for South Africans. Hunter is also a researcher on digital rights and author of a children's book about surveillance, Boris the BabyBot.

iAfrikan: What is the context and background information on these revelations?

Murray Hunter: The most remarkable thing about all this is that we have known for over a decade that the state [South Africa] has been conducting mass surveillance, or 'bulk interception' as they call it - and that it's almost certainly unlawful. The excellent article published by our friends at Privacy International draws on evidence submitted in 2017 by Arthur Fraser, then representing the State Security Agency, in the ongoing court challenge to RICA, SA's surveillance law.

But what's interesting is that Fraser's admissions were actually an attempt at damage-control after the court was made aware of longstanding evidence of the state's mass-surveillance operations.

How far back does this mass surveillance in South Africa date back to?

So, Arthur Fraser said this is all being done according to a government policy adopted in 1999, although whatever that document is remains a mystery, but we had details of the state's mass surveillance activities at least as early as 2006.

That year, the state's intelligence watchdog publicly reported that rogue members of the intelligence agencies had used the SSA's mass-surveillance facility (known as the National Communications Centre or NCC) to spy on political operatives and journalists. (You can download the Inspector General of Intelligence's report)

Then in 2008, the Matthews Commission, appointed by Ronnie Kasrils in the wake of this scandal, confirmed that the government was indeed conducting mass-surveillance through the NCC, and doing so unlawfully. (You can download the Matthews Commission report)

What was "tapped"?

The sources are vague about the details, but if we combine what's in those oversight investigations in 2006 and 2008, and Arthur Fraser's claims in 2017, it suggests that the NCC has been used to do 'bulk interception' of at least 'some' content and metadata from a range of sources, including internet traffic, telephonic communication, and satellite data.

So, they might not be able to collect all of it, at a technical level, but it seems that they're open to trying.

Fraser calls it “broad based environmental scanning”, whereby a great deal of data is collected from any and all sources, and then analysed for key words.

Essentially, the State Security Agency is collecting as much haystack as it can, just in case it needs to look for a needle.

We're talking here about people's most sensitive private information: Internet traffic, communications data. Arthur Fraser has tried to assure the court that this is non invasive because it's done by computers instead of humans, which really shows how out of date the state's thinking is on digital privacy. It's 2019 - of course it's being done by computers, just like nearly all the world's most invasive mass surveillance.

So the government has been quite upfront that it's collecting data from a vast number of people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing, and is analysed for all kinds of purposes. In fact, he says people's communications data is even being analysed for the purposes of food security and water security. So we're not even limited to serious crimes or terrorist acts here - just snooping through people's data to make sure nobody's talking about maize shortages or whatever.

Is this kind of spying legal?

Hell no. As early as 2008 the Matthews Commission warned that this kind of mass surveillance is unconstitutional, but there is *no law* that enables it. The RICA law, as bad as it is, is clearly designed to regulate targeted surveillance - whereby the state MAY be able to intercept the communications of a specific person or group of people, if they are being investigated for the most serious crimes, and if a judge has looked at the case and signed off on it.

There is no way a judge can meaningfully sign-off on the interception of a thousand or a million people's communications data, just in case one of them ends up being suspected of wrongdoing. Evidently, the State Security Agency agrees, because there's no evidence they even try run these operations past the RICA judge.

What is an acceptable form of tapping by the state?

Quite simply, digital surveillance can only be justified when it's limited to the most serious offences, targeted to specific suspects, and subject to independent oversight and transparency. The State Security Agency seems to think this is crazy talk, but the international 'Necessary & Proportionate' offer a world-class 13-point formula for how to do it.

What would be your advice to South Africans regarding protecting against being spied on in this manner?

As individual users, we should always be mindful of what steps we can take – seeking out simple security advisories like the Surveillance Self Defence Guide – but the real lesson here is that we need collection action as well.

The first step is to get informed. Let's read up on this issue. Let's support the work of journalists who are investigating surveillance issues.

Then let's deepen the public debate, because the places where this debate should have happened, like Parliament, have failed us.

Let's put privacy where it should be: as the centrepiece of people's rights in the modern era.

Because ultimately the people of SA don't just need better encryption, we need a better government. And until the state knows that there is a political cost to these abuses, it will never truly respect our privacy.